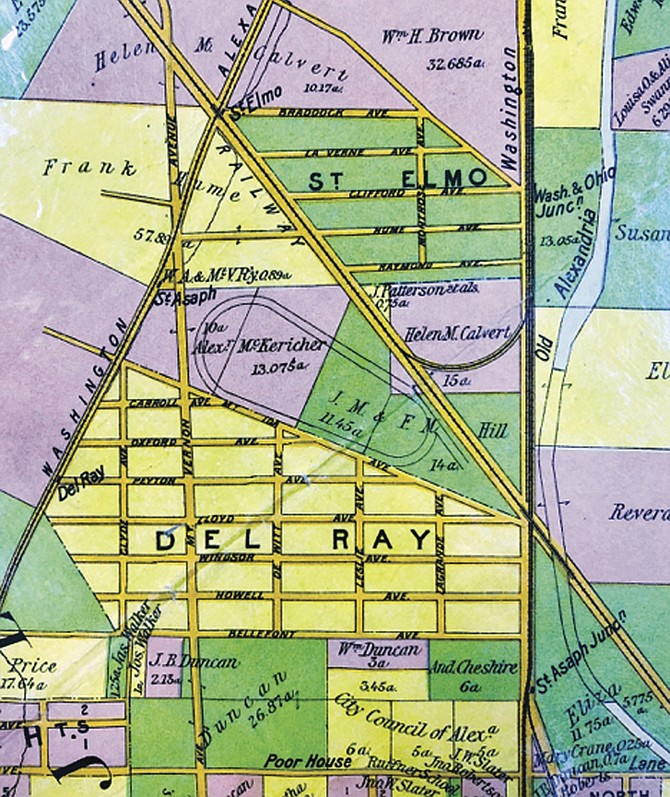

This insurance map from 1900 shows the location of the infamous St. Asaph Racetrack in proximity to the St. Elmo neighborhood and the Del Ray neighborhood. Alexandria Local History Special Collections

Recent years have seen Del Ray emerge into the political and cultural center of Alexandria. The “little neighborhood that could,” as some are fond of calling it, is home to the mayor and the sheriff. Its voting precincts turn elections, and the Mount Vernon Avenue thoroughfare is home to some of the city’s best know restaurants and shops.

But Del Ray has a secret history.

Gambling. Corruption, Racism. Greed. These are all part of a little-known narrative from the neighborhood’s long-ago past, a time when progressive leaders closed a corrupt racetrack and formed the Town of Potomac, only to see an unwanted attempt by Alexandria City Hall to steal the land in a controversial annexation. But this brand of progressivism was also racist, excluding anyone who wasn’t white from living in the newly created town.

“They apparently saw no irony in being progressive and racist,” said Del Ray historian Leland Ness during the 100 year anniversary of the town’s creation in 2008.

THE STORY STARTS in the bad old days of institutionalized corruption. Former Alexandria City Councilman George Mushback used his seat in the Virginia state Senate to introduce a bill that benefited himself personally and politically: the “Mushback Anti-Gambling Bill.” It was a win-win for Mushback, who got the political benefit from being seen as a hard-line opponent to gambling while also lining his pockets.

Unbeknownst to his colleagues in the state Senate, Mushback was also president of the Alexandria Driving Club, a racetrack that would later be known as the Gentleman’s Driving Park at the St. Asaph Junction and ultimately the St. Asaph Racetrack. He didn’t let that stop him from crafting an anti-gambling bill with an ingenious loophole allowing gambling at driving clubs, giving him a secret competitive advantage over the competition.

“As a lawyer, he was eminently successful,” gushed the Richmond Times.

Successful to a point. He certainly had opposition. There was the crusading Commonwealth’s Attorney Crandal Mackey, who was elected on the platform of closing down all the illegal gambling operations in what was then known as Alexandria County. But Mackey did not act alone. He had the help of a 28-year-old printer from Maryland who had just moved to Howell Avenue a few years before in 1895: Joseph Edward Supplee was quoted in the Alexandria Gazette as “defying anyone to prove the racetrack had brought any dollars to the community.

“It kept away good, law-abiding citizens,” he said.

The racetrack was so popular that the railroad brought 1,800 people a day. In 1905, it employed 37 people — one for every house in Del Ray. It attracted violence and destruction, desperate people who attacked farmers and schoolchildren for quick cash. Shutting it down, Supplee said, would “bring a more actual pecuniary benefit than the race tracks could ever accomplish.”

It took a while, but prolonged pressure from Mackey and Supplee eventually paid off. The racetrack closed in 1904. Three years later, Supplee presided over a meeting bringing together residents from the village of Del Ray with the village of St. Elmo — two different communities, both constructed by developer Wood, Harmon and Company, which billed itself as “a suburban real estate company.”

AT THE TIME, folks living in Del Ray and St. Elmo had no electricity, water or sewer system. They were still using outhouses and kerosene lamps. Supplee persuaded his neighbors that incorporating into a town would allow them to negotiate for street lighting and road repair. Instead of being a backwater part of the Jefferson Magisterial District of Arlington County, the argument went, they would oversee their own future and attract new residents.

The idea was a hit, and Del. James Caton and state Sen. Richard Thornton began pursuing legislation in the General Assembly. Caton eventually introduced House Bill 150, which sailed through the legislature without debate. It received final approval on March 13, 1908, and Gov. Claude Swanson signed it into law a few days later.

But the Town of Potomac was not welcoming to everyone.

“The Town of Potomac is probably the most progressive, aggressive and bustling community within the State of Virginia,” boasts a 1924 yearbook published by the Town of Potomac. “It is perhaps the only municipality in the United States in which ownership of real estate is limited to persons of the Caucasian race, and it is also the only municipality so far as known, that does not number among its residents persons of African descent.”

From 1980 to 1930, the Town of Potomac developed into a thriving if insular community — traces of which are still around today. There was the first high school in Arlington County, George Mason High School — now the older part of Mount Vernon Community School. Then there was the building that served as a town hall and fire station, which is currently in use by the Alexandria Fire Department. Plus there was the Palm movie theater, a building that’s currently used by a yoga studio next to Taqueria Poblano.

UNFORTUNATELY FOR THE Town of Potomac, it happened to be right next to some of the most valuable property in the region — Potomac Yard. As early as 1911, the folks at Alexandria City Hall were licking their chops over the potential tax revenues they could pull in from the largest rail yard in America. So they started making moves toward annexing it — essentially stealing Arlington County’s most valuable property out from under it.

The judge of a special annexation court initially dismissed the petition in 1913, but the Supreme Court of Appeals overruled the decision and granted Alexandria part of the land it was seeking — part of the neighborhood now known as Rosemont. That did not satisfy the folks in Alexandria, who still wanted all that tax revenue associated with Potomac Yards. A few years later, in 1927, they were back at it again with yet another annexation petition. The folks leading the Arlington County government were dead set against the idea.

“It will practically destroy the smallest magisterial district in the county, taking 65 percent of its territory, its population, its revenues,” lawyers for Arlington told the court. “This in turn will throw the entire county system of government out of equilibrium.”

The value of the land Alexandria wanted to take in Potomac Yards was assessed at $1.4 million. Tax revenue from the yards was $30,000 a year — a considerable chunk of revenue considering Arlington’s total combined revenue in those days was about $900,000. And then there were all those employees who lived near the yards in the Town of Potomac.

“This was, in fact, the prize that was being sought for so vigorously by both sides to the controversy,” wrote Arlington historian C.B. Rose.

The Potomac Town Council vacillated on the issue of annexation. Initially, council members adopted a resolution in favor of being annexed by Alexandria. But public sentiment was solidly against the idea, and all the council members who approved that resolution were kicked out of office in the next election. The new town council approved a resolution opposing annexation. But the case dragged on for so long that the pendulum swung the other way, and that resolution was rescinded.

In the end, the annexation court sided with Alexandria. But not without a cost. Alexandria was forced to pay Arlington $500,000 for public improvements to the annexed area. They were also forced to assume the debt of the Town of Potomac, which was about $120,000. The residents of Potomac retaliated by throwing all the town records into a giant bonfire instead of handing them over to city officials.